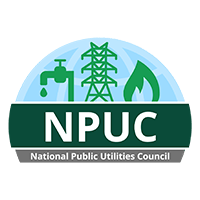

How Droughts Threaten the Future of Hydropower

Hydropower is the largest source of renewable energy in the United States, accounting for 54% of the country’s renewable electricity generation.

However, dry conditions and droughts intensified by climate change are beginning to stress hydropower generation in some regions, casting a shadow of doubt over its future.

The above infographic sponsored by the National Public Utilities Council explores how prolonged dry conditions in some U.S. regions are threatening hydropower generation. This is part two of two in the Hydropower Series.

The U.S. Megadrought

According to a recent study, the American Southwest is currently experiencing its worst megadrought—defined as a drought that lasts two decades or longer—in 1,200 years.

The multi-decade drought that began in 2000 was exacerbated by extreme-dry conditions and a hot summer in 2021. Based on the soil moisture data (covering nine states) used in the study, the 22-year period was the region’s driest spell since 821 AD.

While climate change alone did not cause this, it accounted for 42% of the intensity of the 2000–2021 megadrought. Furthermore, it also made the year 2021 20% drier than it would have been.

As of 2022, California, Nevada, Arizona, Utah, and New Mexico were among the hardest-hit states by dry conditions, which has affected both their hydropower generation and reservoir storages.

Hydropower’s Droughtful Future

In most drought-hit states, hydropower’s share of electricity generation has fallen over the last two decades.

For instance, California’s hydropower generation dropped from 25.5 million megawatt-hours(MWh) in 2001 to 17.3 million MWh in 2022. Over that same period, hydropower’s share of California’s electricity generation fell from 13% to 8%.

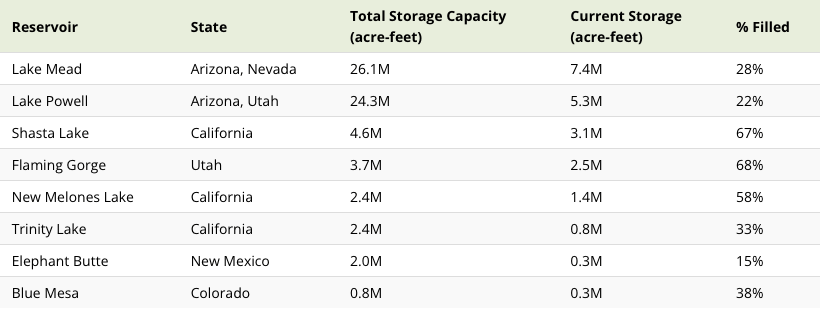

Besides the long-term declines in hydroelectric generation, water levels at some reservoirs are precariously low. Here’s a look at the water storage levels of select Southwestern reservoirs as of March 15, 2023:

Notably, Lake Mead (Hoover Dam) and Lake Powell (Glen Canyon Dam)—the top two largest U.S. reservoirs by capacity, respectively—have alarmingly low storage levels with less than one-thirdof total storage filled.

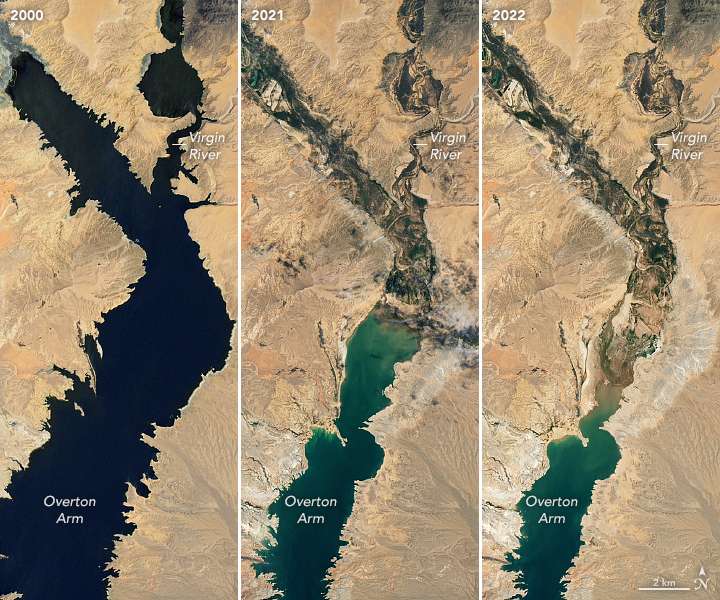

To put that into perspective, these satellite images from NASA show a bird’s eye view of the Overton Arm, a part of Lake Mead, in 2000 compared to 2021 and 2022:

Similarly, prolonged dry conditions have pushed the storage levels of many other Southwestern reservoirs to well below their long-term averages.

The risks from these falling water levels are clear—if a reservoir’s elevation falls below a certain threshold (known as the minimum power pool), it can no longer support power generation. This occurred in 2021 when California’s Edward Hyatt Power Plant was shut down due to historically low water levels at Lake Oroville. Although the plant has resumed operations since then, the emergency shutdown is a recent example of hydropower’s vulnerability to drought.

Mitigating the Risks to Hydropower

Hydropower is one of the most reliable sources of renewable electricity and can operate at all times of the day. Furthermore, hydropower plants are important “black start” resources because they can independently kick-start electricity generation in the event of a blackout.

Consequently, a threat to the future of hydropower also poses risks for the power grid. In fact, in the summer of 2022, the NERC found that all U.S. regions covered by the Western grid interconnection were at risk of energy emergencies in the event of an extreme heat occurrence, because of dry conditions threatening hydropower.

Besides fighting climate change and working to reduce the frequency of intense droughts, here are three ways to combat the challenge facing hydropower while advancing decarbonization:

- Large-scale backup battery storage systems can be built to compensate for falling hydropower generation during severe droughts.

- Buildings and homes can be retrofitted and built with energy-efficient technologies to curb the overall demand for electricity and load on the grid.

- The power grid can be made more climate-resilient by expanding long-distance transmission lines and deploying more solar and wind power in interconnected regions.